There are many ways to build a growth tech business. Some entrepreneurs are able to self-fund or bootstrap their company and quickly build profitability to support growth, but more typically founders need to rely upon some form of investment to make a go of it. From the first investment dollar, funding decisions will have long-ranging effects on the trajectory of the business.

At the start of a business, there is a bit of a chicken-or-egg problem with funding. An entrepreneur is asking an investor to invest in an idea with no tangible evidence it will succeed. If the financing is in the form of debt, then what is the collateral and evidence the business will be able to repay the debt? If the financing is in the form of equity, then the question is what is the business worth, and how much equity are you selling? Entrepreneurs have grand ideas and huge visions with little evidence. Investors want to share the vision, but for the most part they are pragmatic and avoid being swept up in the entrepreneur’s enthusiasm. The result is an imbalance of valuations. The solution is often to follow a crawl-walk-run approach and agree on a small amount of initial funding to get going, so you can prove the business and live to fight another day about the value of the business when seeking a larger investment.

Whether you are an entrepreneur starting a business, a CEO of an ongoing business, or an executive considering joining a company as a hired CEO, every funding decision is of paramount importance. Once you get past friends and family and angel investors, institutional investors follow fairly defined playbooks, and it is vital you understand what you are getting into.

Most PE and VC firms raise closed funds with a fixed amount of capital and a fixed set of limited-partner investors. Funds have investment rules about how much can be invested in a single company, and they generally have an anticipated lifespan during which investments are made and exited so that investors get their money out. Most firms cannot (or will not) cross invest from one fund to another. If an investment is made from fund 1, and a subsequent capital need arises. If fund 1 is tapped out, it is rare that the firm will make a subsequent investment in the same company from fund 2. Often there are different pools of investors, and it gets messy if fund 2 is perceived as bailing out fund 1, or if the outcomes will be different.

As a CEO, when considering an investment from a new VC or PE firm, you want to know the fund dynamics. You are not just considering an investment firm, you also have to consider the fund out of which the firm is investing. You want to know how old the fund is, and how your potential investment compares to the typical investments in this fund. You also want to know the rules of the fund for follow-on investments and if there are limits on how much may be available to your company as well as if the fund has the capacity remaining to make sufficient follow-on investments.

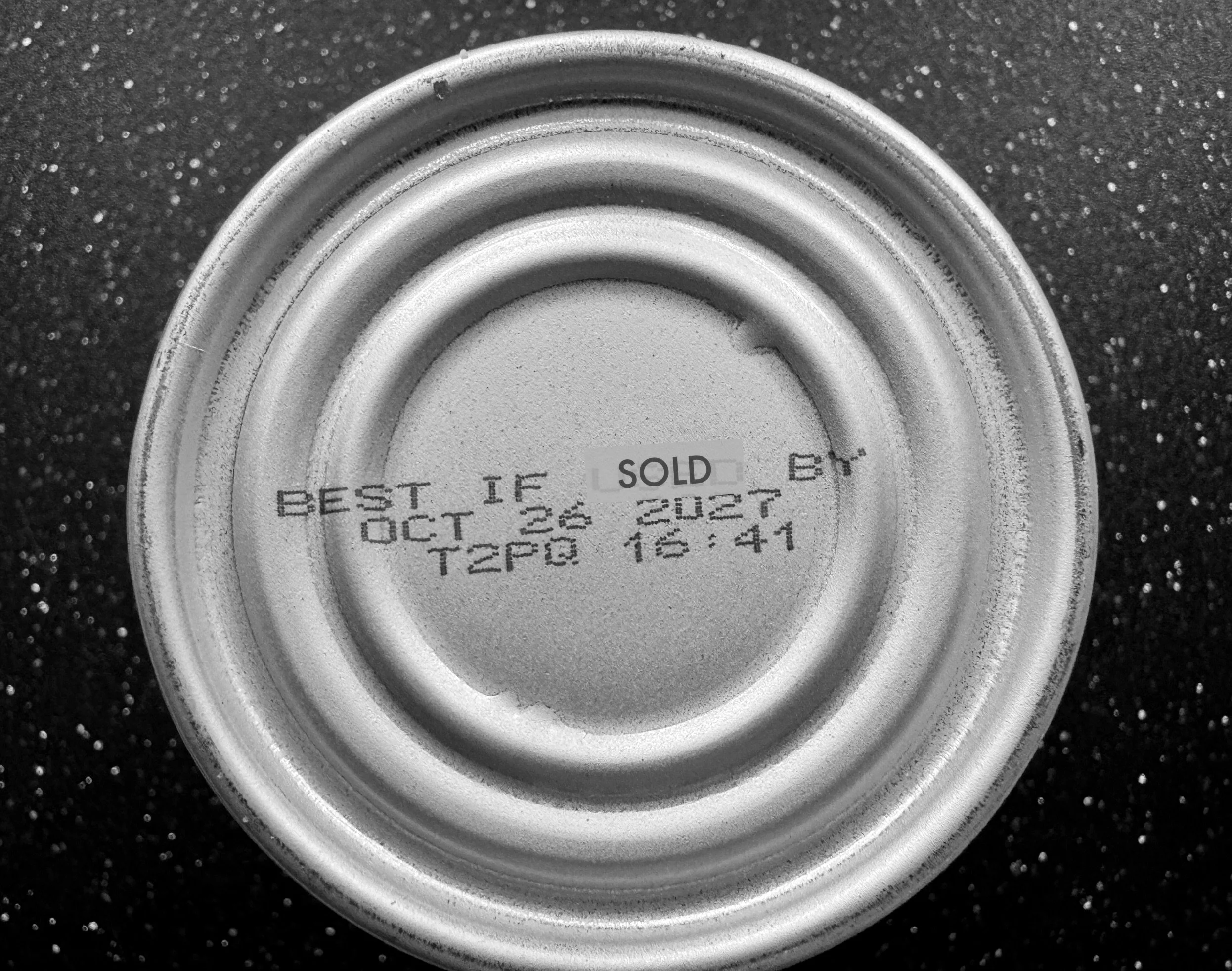

When considering a first institutional investment, the CEO has to recognize that it is a lot like tattooing a “Best if Sold By” date on their forehead. Institutional funds have a lifecycle, and depending upon where the fund is on that timeline when the investment is made, the best-if-sold-by date will be loosely tied to the expected remaining life of the fund. It is a fair question for the CEO to ask and expect an answer that is more than just BS. The CEO and the investor need to be aligned on timing and what success will look like for the fund, as well as what the firm’s expectation is for eventual exit. Nothing will be hard and fast, but there needs to be alignment, and the CEO needs to recognize that the investor is not in it forever.

As the business grows, it will likely need capital and also likely move through the ranks of institutional investors from angels to venture to growth equity and through various larger tiers of private equity potentially to public markets. Each tier of investor has different expectations and tolerances, as well as different timelines. Every single funding decision has long-ranging implications, and this becomes very apparent as the business grows and seeks additional capital moving up the tiers of investors.

Managing board and investor expectations is a major part of a CEO’s job. This is particularly challenging when the firms around the table come from different investor tiers, and they invested at different stages with different expectations. A venture firm may have invested in a technology business with expectations of >50% growth rates, high gross margins, and limited focus on profitability. A subsequent PE investor may expect more modest 30% growth, greater attention to EBITDA, and a longer hold period. For the CEO, this makes setting strategy and measuring success a challenge. Being aware of investment expectations before accepting an investment, and solving for a common ground early will greatly smooth the board / management relationship going forward.

Committing to board seats, granting decision making blocking rights, preferences, and participation rights at early funding stages can become nightmares at later stages. Large-scale professional investors may be unwilling to have Uncle Bill on the board, even though you promised Bill a seat when he gave you seed money to start the company. They will also object to Bill having the right to block an equity decision, or any real say in the business. As an entrepreneur you have to jealously guard all of the rights that will become critical later in the business, and avoid giving up too much too early. Starting out with 100% of the equity, giving away (or selling) too much early on will result in massive dilution after multiple rounds of institutional capital. You may wake up one day and discover you only own a few percent of the business you poured your heart and soul into for years.

Preference stacks and multiples are the bane of an entrepreneurs existence. Institutional investors typically invest in preferred stock, and too often they require multiples of their initial investment before the proceeds trickle down the preference stack to common shareholders (including the entrepreneur founder and team). If the company has gone through multiple rounds of investment, and each round includes a multiplier, it is not uncommon for all of the proceeds of a sale to be distributed to institutional investors and none to the common shareholders. CEOs need to be aware of the preference stack and conscious of how high the bar is being set before the common shareholders make money. Don’t be surprised.

The bottom line is to create a long-range business plan with realistic projections, and anticipate funding needs long before they materialize. Jealously guard against giving up too much too soon. Be aware of all of the tools investors employ to reduce their risk and increase their returns. Sometimes, it is not only a question of enterprise valuation at the point of investment, you also have to consider the dreaded preference stack and multiples and participation rights. Most importantly, the CEO needs to be aligned with and aware of the investors’ time horizons and expectations, and look out multiple years to plot an appropriate strategic funding course.