There is a saying attributed to Steve Jobs (although I'm not sure it actually came from him) – “Never embarrass Apple.” The way I heard it, one of the worst things an Apple employee could do was embarrass the firm. It could be by delivering a bad or faulty product, or it could be by delivering bad customer service, or it could be in messaging, or any number of ways, but if the end result was embarrassing for Apple, then the responsible party had violated a cardinal rule. This simple saying – ‘Never embarrass Apple’ drove a culture that was dedicated to delivering ‘insanely great products’ (another Job’s quote). It focused every team member on guarding the reputation of the company, and it caused team members to have each other’s backs. If a product was not performing well, the ‘genius’ in the store never complained about the poor quality of the engineering or the manufacturing, or the difficulty of the user interface. Instead, they represented Apple. While they may have empathized with the customer over the problem, they addressed it in a professional way with pride in Apple’s dedication to greatness.

With the launch of the new year, a lot of companies reassess their value statements. We have all seen these statements with a predictable list of platitudes. There is nothing wrong with the lists, but often they include aspirational values that do not really reflect the way management and the business operate. “We value customers above all else” rarely translates into valuing customers over profits. “We are one team” often overlooks the politics of the organization. When the lists are presented as core values, if employees know the statements to be hollow, it creates a credibility and trust issue. It also makes it difficult for team members to figure out the true values and how they really ought to behave.

Think about the “Never embarrass Apple” mantra and let it sink in for a minute. It is a simple statement that can pervade every aspect of how a company operates, and what it delivers to customers. It can drive a company to create insanely great products and to deliver insanely great services that “make a dent in the universe” (another Jobs quote). To avoid embarrassment, product implementations need to go smoothly, team members need to deliver services professionally, features need to be complete and wow the customer because anything less would embarrass the firm. If a customer has a problem, we have to exceed their expectation for service. If a product has a defect, we have to eliminate it expeditiously because otherwise it will become an embarrassment. The simple phrase “Never embarrass ‘the company’” embodies a litany of values.

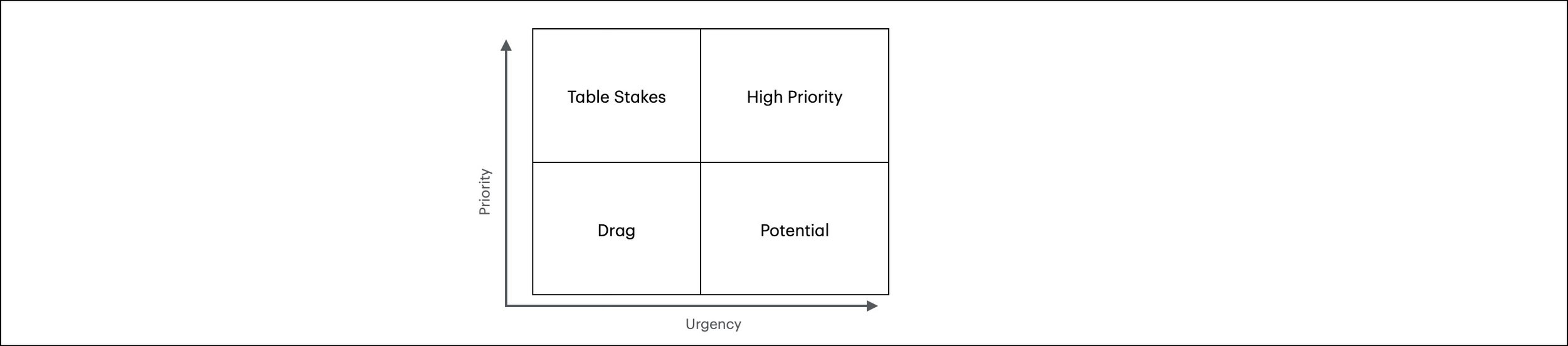

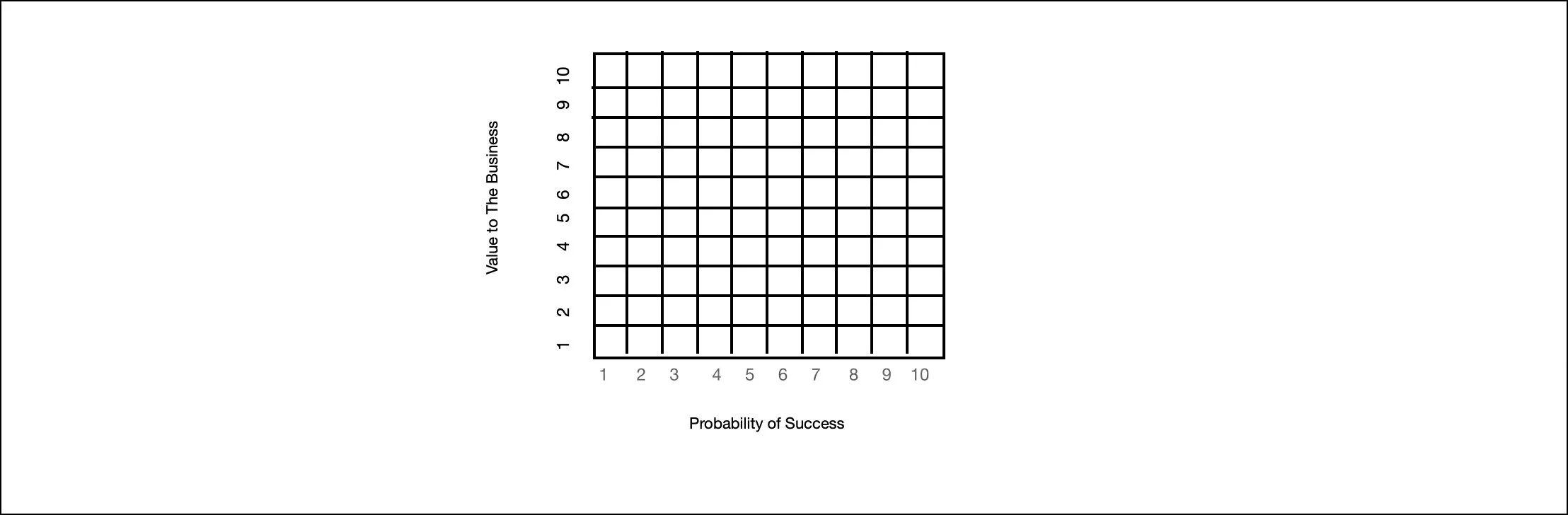

A simple way to think about how to apply the phrase is the PR test —“If a journalist wrote an article describing this action or behavior, would we be proud of it or embarrassed by it?” A customer support person I know once questioned why their company considered some product defects to be minor and not worth fixing. This individual asked how the company would respond if customers knew that the defects they reported were being ignored? The team member went on to say “you might hear statements like “bug-free is hard,” but I can guarantee that it is harder to explain to customers why the defect occurred in the first place… It is my opinion, that bug-free is hard today because we do not emphasize a bug-free environment. If that was a KPI then it is my prediction that being bug-free would get easier with time.” It was a variant of the PR test that highlighted the values-based decision making of senior management with regard to product quality. It also shows how powerful the simple edict “never embarrass the firm” can be.

A quote often attributed to Mark Twain (although he apparently never said it) is “Doing the right thing will never be the wrong thing.” This mantra pairs well with the Steve Jobs quote. ‘Do the right thing’ is a character statement that guides behavior and should never result in embarrassment. When we think about corporate values and consider how to make them meaningful to the team, “do the right thing” and “never embarrassing the company” are about the simplest statements I have found, and they can guide a team more effectively than any list of platitudes every will.