The last couple of posts have been about maximizing employee ROI, and the importance of developing meaningful Mission, Vision, and Values statements to guide the team to a successful outcome. Even when we get it right, there always seems to be occasions when the employee rumor mill takes over and negativity creeps in.

Sometimes, the negativity is in response to actual bad things happening, so it is understandable. Perhaps there was a reduction in force, and the remaining team members are feeling down. Or, the company just lost a big deal, or a major customer just churned. Like a toxin entering the blood stream, a healthy corporate body can respond and ‘metabolize’ the bad news, so the company can move forward. There is a saying ‘that which doesn’t kill you will make you stronger,’ and often recovering from a negative event does make a company stronger.

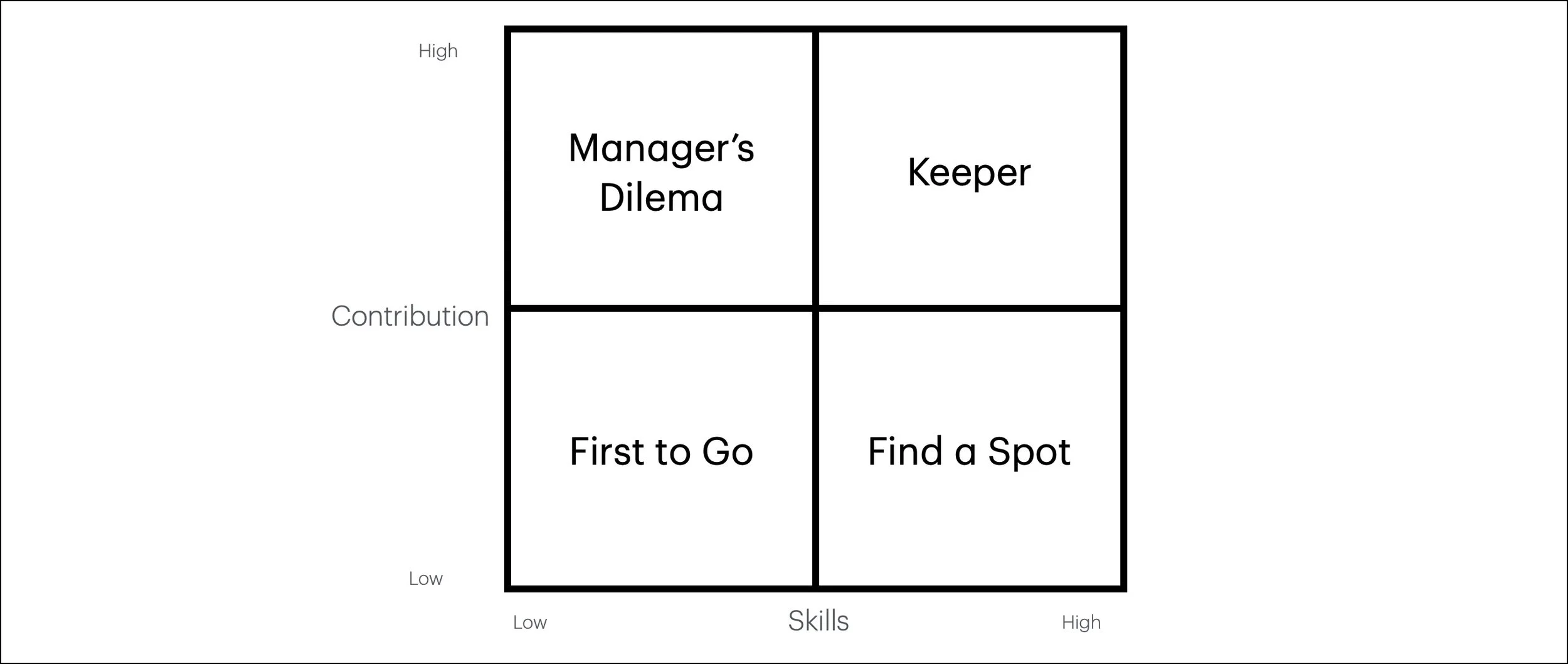

However, sometimes the problem is a hyperactive rumor mill and corporate conspiracy mongering. Corporate grapevines are extremely efficient. Managers think they are shielding the team by keeping secrets, but somehow the staff always figures out that something is going on. Employee rumors often follow what is referred to as the ‘Ladder of Inference,’ and leadership needs to instill a strong mechanism to defuse the ladder.

Suppose that every Friday the company provides bagels in the morning for the staff. Without fail, week after week, the staff shows up and the bagels are waiting. One Friday, Johnny is the first to arrive and there are no bagels. Horror of horrors! Jane is the second person to arrive, and Johnny turns to Jane and says “OMG, there are no bagels! I bet the company did not pay the bill. Maybe we are out of cash?” Mike arrives next, and Jane immediately tells him “the company is out of cash and we are not going to get paid!” Mike turns to the next person and says “the company is broke and going out of business. Quick get your resume on the street…” Finally, Mary the accountant arrives and announces to the panic stricken team that the bagel guy’s truck broke down and he will be a little late.

This is a classic example of a company escalating up the ladder of inference based on a lack of knowledge and a rich rumor mill. In the absence of information, we have a tendency to jump to negative conclusions and quickly climb the ladder of inference to engage others in our negative view. We assume the worst. Part of building a strong culture is developing a posture of continuous communication that will enable the team to stay in a fact-based zone and seek clarity instead of imagining evil intent and bad outcomes. The team needs to embrace the value of being data and information driven, instead of rumor and conspiracy driven.

The key is to be open and support high-volume bi-directional COMMUNICATION! In public places and on trains, the slogan is “if you see something, say something.” The same applies to business (clearly for very different purposes). If an employee sees something they think is wrong, their first instinct needs to be to say something to someone that may be able to offer an explanation, or who can help redress the problem. It is far more productive than imagining evil intent or griping to a colleague.

Leadership’s responsibility is to demonstrate honest and open communications. If employees perceive that they can ask difficult questions without repercussions, and they grow to believe that the answers will be truthful, then the ladder never gets off the ground. When employees feel that management is secretive and hiding things, or worst of all, not honest, then employee paranoia and conspiracy theories take over, and we quickly climb the ladder.